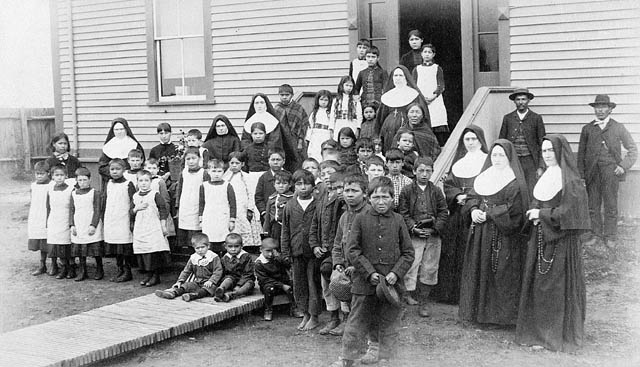

Throughout Canadian history, Indian Residential Schools have been a controversial topic of discussion. As early as the 1840s, Indian Residential Schools were popping up all over Canada to fulfill the views and expectations of the white population towards the Indigenous peoples. The primary goal of these schools was to assimilate the Indigenous children into the more desired European Christian culture, no matter the harm and torment that would come to the children. The children were subjected to appalling living conditions, a variety of abuse and treatments, and forced to learn different curriculum and ways of life, and disregard their previous knowledge. This not only impacted the child, but also influenced their overall childhood and education. Throughout this research essay, I will focus on the province of British Columbia from the turn of the twentieth century to the closure of the last school in 1996. The essay will give a brief overview of the reasons of establishment of the Indian Residential School system and some effects these schools had on children and parents. Progressing through the essay, it will discuss three factors: living conditions, abuse and treatment, and curriculum and ways of life, and how these factors effected the child and their childhood and education in this time.

In the mid 1800s to the latter part of the twentieth century, Indian Residential Schools were popping up all over British Columbia and other parts of Canada. These schools were run by religious orders, primarily of Christian denomination, as well as the State. The main purpose of these schools was “to assimilate Indigenous people by using Christianity to ‘civilize’ the ‘savages’”[1]. It is noted that “for more than a century, Canada’s sustained effort to eradicate the Indigenous culture hinged on targeting the population’s most vulnerable group: its children”[2]. By targeting the Indigenous children first, this made it easier for the white population to implement what they set out to do. To succeed in doing this, schools “were placed far from parental influence [so the children could] learn English, manual labour, [domestic duties], and Christian values”[3]. This was a very strategic move by the Europeans, because to get at the “root” of “the so-called ‘Indian problem’”[4], the best way would be to target the children early and to redirect them into a more respectable culture as opposed to their native traditions and upbringings. By forcibly taking the children at a young age and away from parental influences, this was key to assimilate and “systematically fit them with religious beliefs, social habits, and educational training”[5]. Even though this action done by the white population seeming strategic and well thought through, it was execrable to do such a thing to group of people. Within these schools, “students were stripped of their tribal language, traditions, and spirituality… they were told the only valid historical authority belonged to Canada’s European settlers, not their own elders”[6]. In addition to this, these schools made “Indian children… ashamed of their parents”[7] and of their culture. These schools had some positive connotations to them such as teaching the children English and other duties and values that could be valuable to them later in life. However, to teach and force children to forget and feel ashamed of their past and their upbringing shows how cruel these schools were in their efforts to assimilate the children. No person, especially a child should be subjected to such cruelty and forced alienation of their family and past.

To add to this, “when school attendance became mandatory”[8] parents had no choice but to allow their children to attend these schools. “Indigenous parents were forced to accept their children’s removal from the home under threat of legal actions”[9] and many parents were “sent letters [stating they would] go to jail unless [their children] went to a residential school”[10]. However, these threats did not stop some parents and families from giving up their children to the residential school officials that easily. “Some families withdrew into their traditional territories to keep their children away from the churches and schools… [others] hid their children to protect them”[11]. These ways that the Indigenous parents tried to spare their children from going to these schools shows how deeply they rejected the idea of these schools and did not want to give up their children. However, as years progressed, it became increasingly more difficult to keep their children away from these schools. “It then became punishable by law not only for the children to be out of schools, but also for parents to withhold their children from attending these schools… [not only were they threatened with] arrest for not sending their children to these schools, [but] Indian agents would often withhold food from them, and assert power and control over them”[12]. With actions such as these that were being enforced on the parents, they eventually had no other option but to send their children to these schools. The effort by residential school officials to both forcibly take children away form their parents and family, and also make them feel ashamed of their past and family, shows how appalling these acts by the government and the church were. Parents are an integral part of not just a child’s life and their upbringing, but also impacts their childhood and education tremendously. Therefore, if a parent or a parental figure is not in the life of the child, then their childhood and educational instruction will be hindered and not what is expected of them.

Not only does parental absence in the lives of Indigenous children impact their childhood and education, but also a variety of factors which they endured in Residential schools contributed to this. Children were subjected to horrendous living conditions, unbearable abuse, and treatments, and forced to learn curriculum and new ways of life as opposed to what they have previously learned.

Living conditions were a big issue within these schools. Indian Residential schools were mainly funded by the State and with what little money that was provided for these schools and for each child, it was far from adequate resulting in horrendous living conditions. Living in these schools were not good for any person to live in, especially children of such young ages and who would be there for many years. These conditions that the children lived in would be a prominent negative memory in their childhood. “The schools were poorly built and the children’s living conditions were poor”[13]. Many of the facilities in these schools were not satisfactory for the amount of people that these buildings held. These inadequate facilities that contributed to the bad living conditions, also contributed to health concerns within these school. The schools were “overcrowded, had poor lighting, poor heating and cramped quarters”[14], and “the nature of the present water supply and the so-called toilet system [was] a positive menace to health”[15]. The “toilet facilities and water supply presented problems in the schools, but bathing arrangements were also difficult”[16]. Bathtubs were mainly located in the basement or in corners of the segregated dormitories, “the little ones were bathed first in scalding hot water [then] the older students bathed later in cold, dirty water”[17]. These bathtubs were breeding ground for bacteria and other health concerns and diseases that were prevalent in this time. Heating and air quality within these schools were also a big concern. “To house forty children in a damp building where they are often chilled, and shivering is a fertile ground for diseases”[18]. “Many dormitories had sealed windows in order to conserve heat [however], this led to unbelievably rank atmospheres and foul air [so then] the supervisor would open the windows wide and close off the heat register when the children went to bed” and frequently children would lay in bed teeth chattering[19].

Not only did the children deal with these poor living conditions in terms of facilities, they also had to endure intolerable meals that they were forced to eat. Many children “were forced to eat rotten fish, bad meat, and oatmeal with worms in it”[20], and sometimes the porridge “contained grasshopper legs, bird dropping and mouse droppings”[21]. These meals were not only terrible to eat but also linked to many illnesses and health concerns. These appalling meals that were given to the children were served in a large majority of the schools in British Columbia, however, the schools who did not provide these types of meals were still poorly constructed and ill-equipped to provide adequately for such large numbers of children.

Both poor living conditions and bad food contributed to illnesses and the spread of diseases in many Indian Residential Schools across British Columbia. “There were epidemics like chicken-pox, measles, and mumps”[22]. However, tuberculosis was a very common disease that “was presented equally at every age… the disease showed an excessive mortality in the pupils between five and ten years of age [and the large number of] children demanded”[23] medical attention. However, with lack of funding for facilities within the schools and inadequate meals for the children, providing heath care for them was also a very low priority. “Little medicine was available to treat the children, and home remedies were often used… and many [children] were moved to isolated wards”[24] so there was less risk of spreading the illness. For a child to have to deal with illnesses and also the worry of death, and with no help from adults with poor treatment provided, this greatly affected child.

These conditions that the children dealt with while living in these schools were far from adequate for any individual to live in. These memories of going to bed cold and dirty, going through the day hungry, and sometimes dealing with illnesses was a prominent childhood memory for many Indian Residential School survivors. These conditions greatly effected the child and their childhood. No child should have to endure such conditions and experiences in their life, however, these memories greatly contributed to their terrible childhood.

To add to the inadequate living conditions that Indigenous children had to deal with while attending these schools, they also had to endure abuse and harsh treatments. Many children in these schools were subjected to “physical and sexual abuse, and humiliation”[25]. This not only greatly effected the child, but also their childhood experiences, and the memories they had in this time of their life. Physical abuse was very common in Residential Schools and was given for a variety of reasons such as speaking their native language, laughing, or disobeying any rules of the schools. Some officials would “beat [the children] with a conveyor belt strap three inches wide and three feet long”[26], others would used pant belts as weapons of authority over the children, whereas some would spank the children. “The old saying ‘spare the rod and spoil the child’”[27] was likely a reason for such harsh physical abuse in these schools, because many believed that harsh physical punishment was the way to “kill the Indian, save the man”[28]. Therefore, this type of punishment was seen as rational to enforce within these schools, even though it was cruel to do so. These forms of physical punishments not only effected the child, but also their childhood experiences, because no person should have to endure such treatments, and these childhood memories of physical abuse left a lasting impact on them. In addition to physical abuse, there was sexual abuse that also took a dramatic toll on the children and their childhood memories and experiences. In many schools, many of the male officials would take advantage of the younger children. Rape and molestation were common, which emotional and psychologically scarred the children at every age. Even more commonly, both physical and sexual abuse coincided with each other, making these experiences of abuse even more traumatic and damaging. It is noted than many of the children “who were raped in the infirmary at night [would also be] hit on the back of the head with the strap”[29].

Physical and sexual abuse were both traumatic events in the children’s lives, however, humiliation was also a prominent form of treatment in these schools. When the children first got to the school, they “were given immediate humiliation”[30]. The school officials “expected [the children] to speak English only and immediately… [and the children] were deloused, DDT put in their hair, then shaved off”[31]. Humiliation was a key punishment technique that the school officials enforced on the children. Most punishments such as the strap and spanks were given publicly, which was both humiliating and degrading to the child. “The strap was given publicly… [and the officials would take the children’s] pants down and lean them over a bench in front of everybody”[32]. Punishment and public humiliation with the strap was very common, however, other means of humiliation were also publicly displayed throughout the school. If children wet the bed “their wet sheets were put over their heads and then they were spanked”[33]. Public mortification in any aspect greatly effected the child and had a negative impact on their childhood. To have to be subjected to these forms of humiliation and treatments harmed them and influenced their childhood experiences and memories, being full of abuse and torturous humiliations and treatments. No child should have to endure such actions throughout any part of their life.

Going away from abuse and treatment, another factor that influenced the child and their childhood and education was their curriculum and the ways of life they learned while attending these schools. English was the main language that the children were taught, however, some schools implemented French as well, and with this, the children’s native languages were disregarded. “Indigenous languages came under attack, and English and French were imposed on Indigenous children”[34]. This was a very difficult transition for children at any age to go from speaking their own language, then having to learn a completely different language and not utter a word of their previous language. This factor in their curriculum vastly impacted their education that they would receive at these schools. Progress for children in the schools was sometimes slow and difficult because the teachers did not teach effectively or efficiently and frequently imposed punishment on the children if they could not comprehend the languages. “Religion was also an integral part of all Residential school curricula… In Catholic schools, hours and hours were devoted to learning the catechism”[35]. The “concept of Christian education”[36] was very prominent in this time, because it was believed that it was a more respectable religion and educational standard to teach the Indigenous children. Religion was just one “education model used to assimilate and civilize Aboriginal”[37] children. This form of education had many aspects to it, such as praying, which was implemented at mealtime, bedtime, and at church services that was mandatory to attend. This new form of education effected the child because they had to learn completely new languages then what they had previously learned and different religious beliefs as compared to their own traditions.

Another form of education they were taught was labour and domestic skills. It is noted that in some schools, most of their curriculum and school day was geared towards labour work. “Two hours of school was given each day [and] the rest of the time was labour done in the school… washing walls and windows, doing all the chores”[38]. In addition to this, other tasks included tending to the farmland and animals which some schools had on their property. In some respects these skills that the children were taught could help them later on, however, at that moment these laborious tasks that the children had to do was not something they should be doing. Overall, these schools had a few different forms of education that was implemented into the children’s daily lives. Learning both English and French, the Christian religion, and lastly domestic and labour skills could help the children in their future, however, some of these forms of education at the time being were not acceptable to enforce on the children, which overall influenced the child greatly and their childhood and education.

Indian Residential Schools were a prominent part in the history of Canada. From the turn of the twentieth century to the last few years when the last school closed in 1996, these schools effected the Indigenous children and their childhood and education. In the beginning, the main reasons for these schools was to forcibly take Indigenous children from the families, traditions, and cultures, and place them in Residential schools to assimilate and civilize them into a more respectable European Christian culture. This greatly impacted parents, the children, and their childhood and education. The children who attended these schools endured a variety of things that significantly affected them. These factors include, horrendous living conditions such as lack of adequate facilities and meals, that contributed to health and other medical concerns. Physical and sexual abuse, and humiliating treatments the children were subjected to. Lastly, new education and ways of life, such as learning the English and French language, the Christian religion, and domestic and labour skills that were enforced on them. All of these factors not only tremendously effected and influenced the children, but also their childhood memories and experiences, and their overall education they received in this time.

Endnotes:

[1] Erica Neeganagwedgin, “‘They can’t take our ancestors out of us’: A brief historical account of Canada’s residential school system, incarceration, institutionalized policies and legislation against indigenous peoples,” Canadian Issues, (Spring 2014): 32.

[2] Daniella Zalcman, “‘Kill the Indian, Save the Man’: On the painful legacy of Canada’s residential schools,” World Policy Journal 33, 3 (Fall 2016): 74.

[3] Erica Neeganagwedgin, “‘The can’t take our ancestors out of us,’” p. 32.

[4] Noel Dyck, Differing Visions: Administering Indian Residential Schooling in Prince Albert 1867-1995, Halifax: Fernwood Publishing and Prince Albert: The Prince Albert Grand Council, 1997: 14.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Daniella Zalcman, “‘Kill the Indian, Save the Man,’” p. 75.

[7] Noel Dyck, Differing Visions, p. 14.

[8] Erica Neeganagwedgin, “‘They can’t take our ancestors out of us,’” p. 33.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Concerning abuse at the United Church Native Residential School, Port Alberni (1945-1950), Testimony of Harriett Nahanee, given to Rev. Kevin McNamee-Annett, North Vancouver, (December 14, 1995): 1.

[11] Erica Neeganagwedgin, “‘They can’t take our ancestors out of us,’” p. 33.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Agnes Grant, No End of Grief: Indian Residential Schools in Canada, Pemmican Publications Inc., 1996: 112.

[15] Deadly conditions at Ahousaht residential school, described by principle, Indian Agent’s Office, Port Alberni, B.C., February 8, 1929, (January 30th, 1929).

[16] Agnes Grant, No End of Grief, p. 113.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Deadly conditions at Ahousaht residential school, described by principle, Indian Agent’s Office, Port Alberni, B.C., February 8, 1929, (January 30th, 1929).

[19] Agnes Grant, No End of Grief, p. 114.

[20] Kitimat Reserve: Hanna Grant; Deceased, Royal Canadian Mounted Police Document, Prince Rupert, B.C. Ocean Falls, B.C., (June 13, 1922): 2.

[21] Agnes Grant, No End of Grief, p. 115.

[22] Ibid., 126.

[23] Peter H. Bryce, Record of the Health Conditions of the Indians of Canada from 1904 to 1921, in The Story of a National Crime Being An Appeal for Justice to the Indians of Canada, Ottawa, Canada: James Hope & Sons, Limited (1922): 5.

[24] Agnes Grant, No End of Grief, p. 131.

[25] Erica Neeganagwedgin, “‘They can’t take out ancestors out of us,’” p. 34.

[26] Concerning abuse at the United Church Native Residential School, Port Alberni (1945-1950): 1.

[27] Celia Haig-Brown, Resistance and Renewal: Surviving the Indian Residential School, Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Pres, 1988: 82.

[28] Daniella Zalcman, “‘Kill the Indian, Save the Man,’” p. 79.

[29] Concerning abuse at the United Church Native Residential School, Port Alberni (1945-1950): 1.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Celia Haig-Brown, Resistance and Renewal, p. 83.

[33] Ibid., 83-84.

[34] Erica Neeganagwedgin, “‘They can’t take our ancestors out of us,’” p. 34.

[35] Agnes Grant, No End of Grief, p. 173.

[36] Celia Haig-Brown, Resistance and Renewal, p. 62.

[37] Sarah de Leeuw, “‘If anything is to be done with the Indian, we must catch him very young’: colonial constructions of Aboriginal children and the geographies of Indian residential schooling in British Columbia, Canada,” Children’s Geographies 7, 2 (May 2009): 129.

[38] Concerning abuse at the United Church Native Residential School, Port Alberni (1945-1950): 3.

Bibliography:

Bryce, Peter H. Record of the Health Conditions of the Indians of Canada from 1904 to 1921. In The Story of a National Crime Being An Appeal for Justice to the Indians of Canada. Ottawa, Canada: James Hope & Sons, Limited, (1922): 3-18.

Concerning abuse at the United Church Native Residential School, Port Alberni (1945-1950). Testimony of Harriett Nahanee, given to Rev. Kevin McNamee-Annett. North Vancouver, (December 14, 1995).

Deadly conditions at Ahousaht residential school, described by principle. Indian Agent’s Office, Port Alberni, B.C., February 8, 1929, (January 30th, 1929).

Dyck, Noel. Differing Visions: Administering Indian Residential Schooling in Prince Albert 1867-1995. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing and Prince Albert: The Prince Albert Grand Council, 1997.

Grant, Agnes. No End of Grief: Indian Residential Schools in Canada. Pemmican Publications Inc., 1996.

Haig-Brown, Celia. Resistance and Renewal: Surviving the Indian Residential School. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 1988.

Kitimat Reserve: Hanna Grant; Deceased. Royal Canadian Mounted Police Document, Prince Rupert, B.C. Ocean Falls, B.C., (June 13, 1922): 1-4.

Leeuw de, Sarah. “‘If anything is to be done with the Indian, we must catch him very young’: colonial constructions of Aboriginal children and the geographies of Indian residential schooling in British Columbia, Canada.” Children’s Geographies, 7, 2, (May 2009): 123-140.

Neeganagwedgin, Erica. “‘They can’t take our ancestors out of us’: A brief historical account of Canada’s residential school system, incarceration, institutionalized policies and legislation against indigenous peoples.” Canadian Issues, (Spring 2014): 31-36.

Zalcman, Daniella. “‘Kill the Indian, Save the Man’: On the painful legacy of Canada’s residential schools.” World Policy Journal, 33, 3, (Fall 2016): 72-85.

Reflection:

The reason why I decided to incorporate my research paper into my ePortfolio is because it is an important paper of my research project. My research paper deals with the segregation and discrimination of Indigenous children, which is a key aspect I want to discuss throughout my ePortfolio. This research paper helps me to support my argument of how segregation and discrimination can effect the child and their childhood and education.

Header Image from: https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/framingcanada/045003-2430-e.html

Leave a Reply